Context

.~*~.¸¸.~*~.¸¸.~*~.¸¸.~*~.

Though both men were symbols of the rugged American West, their visions for the country were miles apart. Their relationship soured over three primary issues:

- The Indian Removal Act: Crockett was one of the few voices in Congress to denounce Jackson’s plan to forcibly relocate Native Americans from their ancestral lands. Crockett viewed the policy not just as a violation of existing treaties, but as a “cruel and unjust” act that went against the very laws of the land.

- Land Rights for the Poor: The fight became personal when Jackson moved to evict “squatters”—poor American settlers who had built homes on unsurveyed land in western Tennessee. Many of these settlers were Crockett’s own constituents. When Jackson proposed selling that land to wealthy investors instead of the people living on it, Crockett’s respect for “Old Hickory” turned into pure contempt.

- The National Bank: By 1834, the friction reached a breaking point. Crockett abandoned Jackson’s Democratic Party entirely, joining the rival Whigs. He became a vocal critic of Jackson’s war against the Second Bank of the United States, arguing that the President was overstepping his executive authority.

On Christmas Day, 1834, in a letter to a friend, Crockett added a threat. If he’s defeated for re-election to Congress the next year, he will leave the country.

The Fallout

Crockett’s refusal to back Jackson came at a high price. Jackson’s political machine worked tirelessly to unseat him, and they did. It was after this final political defeat that a frustrated Crockett famously told his constituents, “You may all go to hell, and I will go to Texas.”

The Hope of Seeing Better Times

The reflective calm of Christmas Day was overshadowed by his deep-seated loathing for President Andrew Jackson and his political heir, Vice President Martin Van Buren. The Tennessee firebrand spent the holiday not in celebration, but in a moment of intense frustration, pouring his bitterness onto a letter to a friend.

Crockett viewed the current administration with unforgiving contempt, seeing his political opponents as actively dismantling the American Republic, focusing on Jackson’s perceived reckless foreign policy threats and the pressure he put on fellow politicians to abandon their principles.

Crockett asserted that Jackson demanded total loyalty, expecting votes to be traded like “promissory notes”, a condition he deemed destructive to liberty. “Volunteer Slavery” to Jackson, he called it. Van Buren was equally despised; Crockett saw the Vice President as a sly, cunning figure who would simply continue Jackson’s autocratic path.

Overwhelmed by the fear that American citizens would meekly accept this tyranny, Crockett made a dramatic, desperate declaration: if Van Buren were elected president, he would leave the “united States” altogether. He threatened to seek refuge in the wilderness of Texas, claiming even that frontier would feel like a paradise compared to living under Van Buren’s “kingdom.”

Despite the hope and spirit of the holiday, Crockett could only offer a dark assessment of the nation’s decline, closing his letter with nothing more than a faint wish for better times to come.

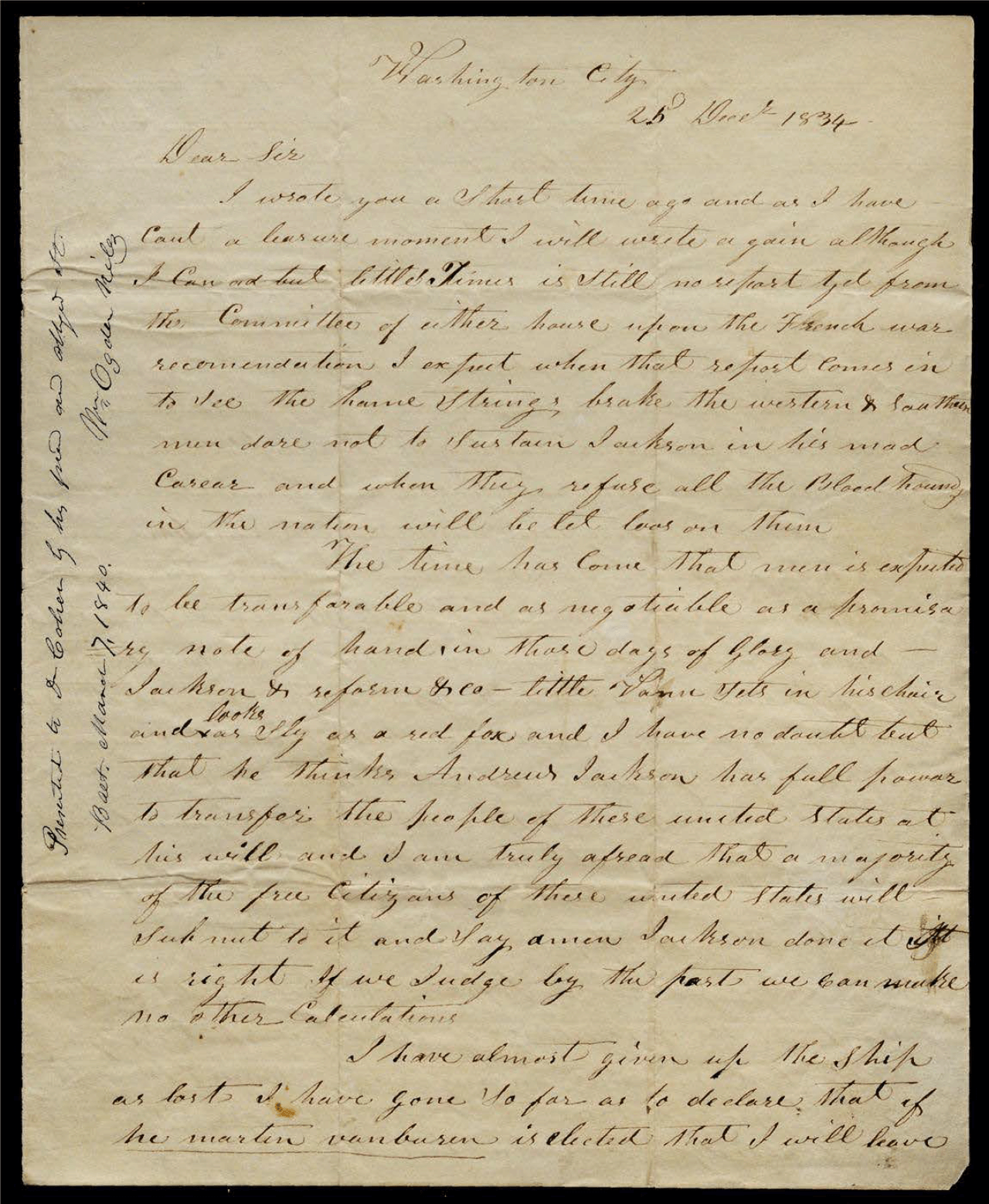

David Crockett to Charles Schultz

Washington City, 25 December 1834.

Autograph letter signed, 2 pages.

Washington City

25 Dec 1834

I wrote you a Short time ago, and as I have a leasure moment I will write again although I can ad but little. Times is still no report yet from the Committee of either house upon the French war recommendation. I expect when that report comes in to see the home strings brake the western & Southern men dare not to Sustain Jackson in his mad Carear, and when they refuse all the Blood hounds in the nation will be let loos on them.

The time has Come that man is expected to be transfarable and as negotiable as a promisary note of hand, in those days of Glory and – Jackson & reform & co.– little Vann Sets in his chair and [inserted: looks] as Sly as a red fox, and I have no doubt but that he thinks Andrew Jackson has full power to transfer the people of these united States at his will, and I am truly afread that a majority of the free citizens of these united States will Submit to it and Say amen Jackson done it. It is right If we Judge by the past we can make no other Calculations.

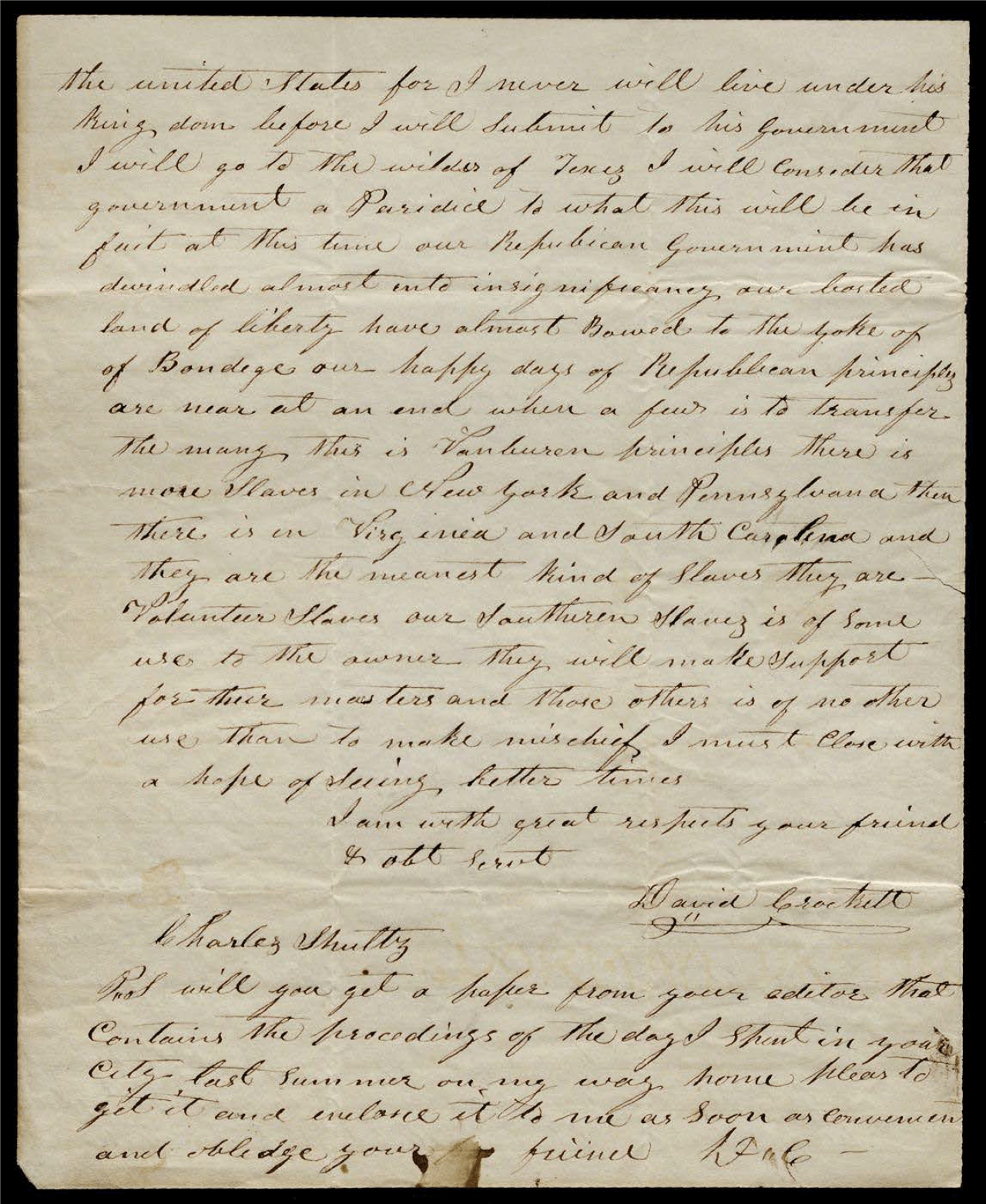

I have almost given up the Ship as lost. I have gone So far as to declare that if he martin vanburen is elected that I will leave [2] the united States for I never will live under his kingdom. before I will Submit to his Government I will go to the wildes of Texas. I will consider that government a Paridice to what this will be. In fact at this time our Republican Government has dwindled almost into insignificancy our [boasted] land of liberty have almost Bowed to the yoke of of Bondage. Our happy days of Republican principles are near at an end when a few is to transfer the many. This is Vanburen principles, there is more Slaves in New York and Pennsylvania then there is in Virginia and South Carolina, and they are the meanest kind of Slaves they are – Volunteer Slaves. Our Southern Slaves is of Some use to the owner. They will make Support for their masters, and those others is of no other use than to make mischief. I must Close in a hope of Seeing better times

I am with great respects your friend

& obt Servt.

David Crockett

Charles Shultz

P.S. will you get a paper from your editor that Contains the procedings of the day I Spent in your City last Summer on my way home pleas to get it and enclose it to me as soon as convenient and oblidge your friend D.C.

[written on margin of first page]

Presented to Dr. Cahern by his friend and obliged svt.

Baet. March 7, 1840 Mr. Ogden Niles

Why Historify?

I discovered the power of story as a history teacher, and the singular privilege of working at a Texas state archive filled with letters penned by people whose thoughts, attitudes, and experiences reflect the times in which they lived.

This simple website was created as a free, uncomplicated, and time-saving introduction to the richness and value of historical sources.

Please join me as we study the past through the words of those who lived it, one life at a time, and thank you for being here.

Buck

Why Historify?

I discovered the power of story as a history teacher, and the singular privilege of working at a Texas state archive filled with letters penned by people whose thoughts, attitudes, and experiences reflect the times in which they lived.

I discovered the power of story as a history teacher, and the singular privilege of working at a Texas state archive filled with letters penned by people whose thoughts, attitudes, and experiences reflect the times in which they lived.

This simple website was created as a free, uncomplicated, and time-saving introduction to the richness and value of historical sources.

Please join me as we study the past through the words of those who lived it, one life at a time, and thank you for being here.

Buck